Nordic Perspectives into the Cold War Art Exhibitions

Maija Koskinen

At the end of August 2021, I participated in a closing meeting of The Centre-Periphery Divide? – Scandinavian Network for Exhibition Studies by the seashore in Saltsjöbaden just outside Stockholm. I presented preliminary conclusions on my current research topic The American Home exhibition (1953) in Helsinki. Some conclusions focused on the nature of the American design exhibition as an example of US Cold War cultural diplomacy. Others dealt with the question of centre-periphery in this state-run exhibition touring in Scandinavia in the early 1950s: the heyday of world famous “Scandinavian design” brands.

The centre of the Western world was the United States,

but the centre of design was peripheral Scandinavia.

Where then was the centre and where was the periphery in an exhibition

showcasing the superpower hegemony?

The question of centre-periphery has been the key question of the Scandinavian Network, established by the University of Södertörn (Stockholm), and its research project Exhibiting Art in a European Periphery? International Art in Sweden during the Cold War.

The network has brought together Nordic art historians who address exhibition studies and the concept of centre-periphery when studying the relations between the international art scene and the Nordic countries after World War II. The researchers from Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland have examined the presence of international art and art exchange in different local, national and Nordic art scenes. The aim has been to challenge simplified dichotomies between East and West, North and South, national and international, capital and region, by focusing more on the question of centre-periphery.

The series of network meetings began in August 2019 in a conference hotel, Rosersberg Slott, with a ‘royal touch’: the hotel was once a palace of the Swedish royal family.[1] In this royal ambiance we analyzed how our research topics address the questions of centre-periphery theoretically or methodologically. Based on my recent PhD thesis, on the exhibition policy of Kunsthalle Helsinki my paper dealt with the international Cold War art exhibitions in the Finnish art field, 1944–1968.

Then all hell broke loose in the form of a global pandemic, and the next network meeting in June 2020 took place online. Instead of presenting papers we discussed the differences in strategies that the Western countries adopted when developing their art scenes based on their geopolitical position and national politics after the war. The discussion was based on an online lecture by associate professor Cathrine Dossin from Purdue University (Indiana, USA) and her recent book, The Rise and Fall of American Art, 1940–1980s: A Geopolitics of Western Art Worlds (2016).

Dossin’s research made me summarize how the story went in Finland. After the war Finland aimed at political neutrality between the East and the West. In the 1950s the Finnish art field favoured l’art pour I’art and reached out for Paris. It no longer found a sensible answer to the pre-war demands on national Finnish art anymore, but found new Italian art encouraging. On the other hand, both new American art and Soviet social realism were considered too strange, albeit for different reasons.

Like Dossin stated, there is not just one story, but stories. That is why the objective of the Academy of Finland project Mission Finland, to introduce the “Finnish case” to the field of international Cold War research, is so important. The trajectory of the cultural Cold War in Finland can turn out to be unexpected.

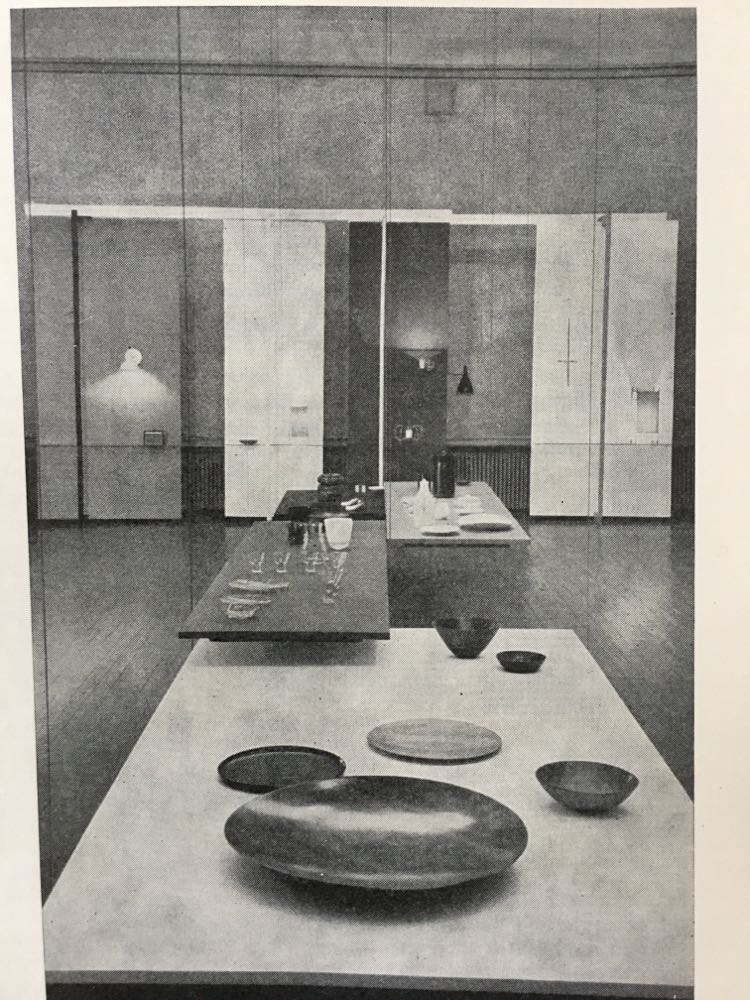

MoMA’s part of the American Home exhibition in Kunsthalle Helsinki in 1953: American Design for Home and Decorative Use.

Image: Arkkitehti – Arkitekten 11/1953.

The Scandinavian network has encouraged collaboration and the exchange of ideas, as well as produced interesting research results among the Nordic scholars. It has been inspiring to meet other art historians dealing with the Cold War art exhibitions – after all I am the only art historian in the Mission Finland project.

Next to inspiration and new perspectives, the network has offered my research a central point of reference. A Cold War art exhibition was typically a circulating one, and the superpowers considered certain regions, like Scandinavia, as one geopolitical unit. That is the reason why American and Soviet exhibitions circulated often successively in the Nordic countries.

As the Finnish representative in the network, it has been important to add the Finnish case into the Nordic Cold War art scene. I have noticed that Nordic art historians do not direct their attention to Finland often enough. For my part, I hope to change this situation by stressing the Nordic dimension in my research. I’ll have an opportunity to strengthen further the Nordic dimension as a visiting researcher at the University of Södertörn in the Spring 2022. I am looking forward to that!

[1] Today part of the Slott, originating from the late 18th century, serves as a Royal Palace Museum.

centre-peripherycirculating art exhibitionCultural Cold WarCultural DiplomacyScandinavia

Blog »